Imagine this scenario: you had a damn good day today. This morning you got a free ice cream cone, a free ticket to the nicest hotel in your area, and you even won a pair of VIP concert tickets to your favorite band’s performance, which had been sold out since last year. Since you are rightly pumped about this day you decide to take the scenic route by the railroad tracks on your way home from work. However, you see something peculiar along the split track…

One person is tied to the railroad track. You aren’t close enough to hear their screams, but upon further observation, you realize that on the other track there are five people tied up! For a moment you begin speculating about the reality of the situation, though this thought is cut short as you notice the train barreling down the tracks towards the five people, who are really screaming and crying now.

Unfortunately, this is where your lucky day takes a turn for the worst. You are the only one around to see this horrendous accident, and you’re way to far to reach everyone in time. Although, you do notice one peculiar thing… the conductors box is right next to you– meaning the train is controlled externally! You have the opportunity to change which track the train travels over. Will you flip the switch so that it heads towards the single individual tied to the track, or will you leave it be to kill the five people already in its grasps?

This ethical dilemma is known to many philosophers as the Trolley Problem. The dilemma here attempts to reach a solution to the nature of how one ought to make a moral decision.

The way in which one may approach the Trolley Problem depends quite a bit on the moral dimensions that one determines to be most relevant. Some aspects of this problem that a philosopher could deem as relevant include: number of people killed, contributions to society made by those whose lives are at stake, morality of those involved (eg, are there any doctors or political figures on the track), personal investment in those on the track (eg, is you mama on that railroad?!), etc. So you see how ethical discussions can become incredibly muddled as a new layer of the potential solution is discovered? While some may believe that the moral thing would be to save the many over the few, others may assert that there is always something inherently wrong with killing no matter how many you might save.

You might have no qualms about pulling the lever as you feel that benefit to the number of people you will save outweighs the harms of killing one person. If you think this, you might be a Utilitarian!

Utilitarianism is a theory that holds that the best way to make a moral decision is to look at the potential consequences of each available choice, and then, one should pick the option that either, does the most to increase happiness, or does the least to increase suffering. Utilitarianism, also known as consequentialism, is often summed up as a philosophy of “The greatest good for the greatest number.”

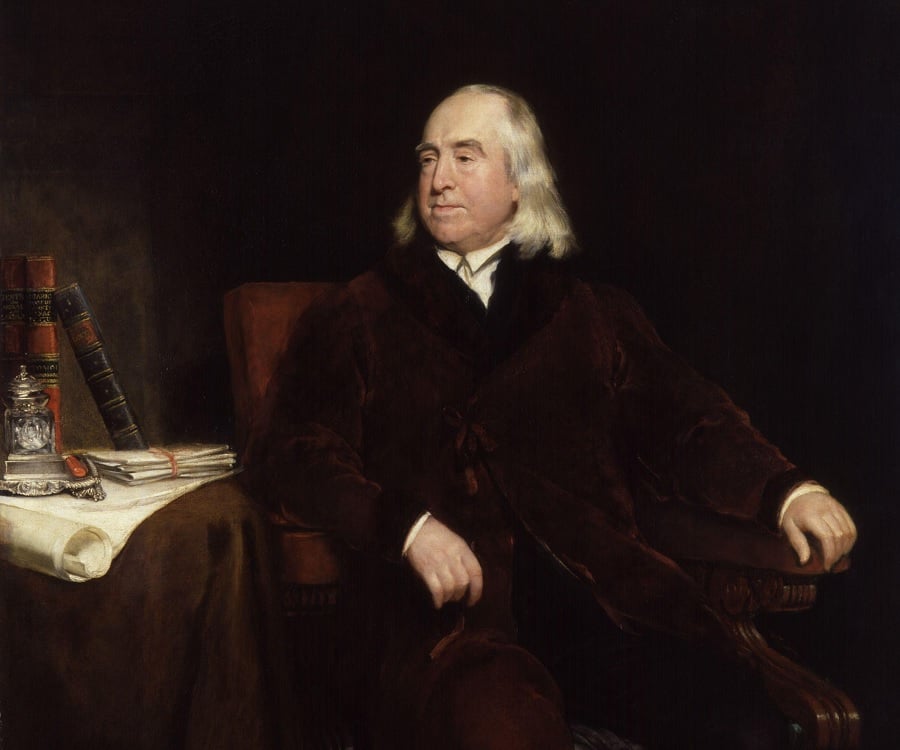

Pioneers of Utilitarianism

Bentham, widely considered one the greatest philosophers of the 19th century, was unsurprisingly, a child prodigy. By the age of three, he began studying scholarly texts, and just a few years later, he began to study Latin and Greek. At the age of 12, Bentham entered Oxford University and begin training as a lawyer, where he first began picturing how he might reform the political structure of society.

Create all the happiness you are able to create: remove all the misery you are able to remove. Every day will allow you to add something to the pleasure of others, or to diminish something of their pains. And for every grain of enjoyment you sow in the bosom of another, you shall find a harvest in your own bosom; while every sorrow which you pluck out from the thoughts and feelings of a fellow creature shall be replaced by beautiful peace and joy in the sanctuary of your soul.

Bentham often emphasized the instrumental measurement of happiness in an act: acts which lead to the most measurable utility (pleasure) are good acts, while those which lead to pain are not. An act is wrong, or right, according to Bentham, inasmuch as it results in a decrease or an increase of overall happiness. In other words, Bentham rejected the notion that any act could be intrinsically wrong or right regardless of consequences.

Moreover, as a strident proponent of social reform, Bentham maintained his Act Utilitarian view by differentiating between moral antipathy to an act and physical antipathy to an act. An example of such is Bentham’s take on homosexuality. He specified that the act in itself gives the homosexual person pleasure, whereas the pain that the dissenting individual feels is not of a moral nature, but rather a preferential one. To this Bentham might say.. “What’s it to you? Look away then.” This idea further resonates with Bentham’s assertions that no act in and of itself is wrong– rather the negative, or immoral, consequences that stem from an act may prove it to be.

Bentham recommended measuring utility in the observation of seven different characteristics associated with a certain act:

- intensity: how strong the pleasure or pain is

- duration: how long it lasts

- certainty: how likely the pleasure or pain is to be the result of the action

- proximity: how close the sensation will be to performance of the action

- fecundity: how likely it is to lead to further pleasures or pains

- purity: how much intermixture there is with the other sensation

- extent: the number of people affected by the action

Driver, Julia, “The History of Utilitarianism”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2014/entries/utilitarianism-history/>.

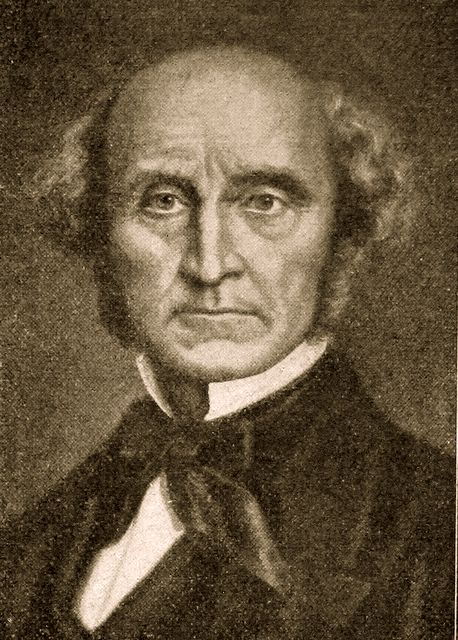

Child prodigy 2.0, John Stuart Mill began speaking Latin by the age of three. By the age of 16, he had a pivotal government position, and by the age of 20 he had a mental breakdown… relatable.

Mill often criticized Bentham’s approach as too egalitarian. Mill, instead, believed that there were “higher” forms of pleasure, more virtuous than those of a “lower”, animalistic nature.

Mill might argue that reading a book is more virtuous a pleasure to seek than is drinking a cranberry vodka. In that same vain, perhaps it is better to be a human in suffering, rather than a swine happily rolling in mud. In this way, Mill asserted that this hedonistic tendency in humans is intuitive in a perfectionistic sense, almost. No wonder Mill had a breakdown!

The only freedom which deserves the name is that of pursuing our own good in our own way, so long as we do not attempt to deprive others of theirs, or impede their efforts to obtain it. Each is the proper guardian of his own health, whether bodily, or mental or spiritual. Mankind are greater gainers by suffering each other to live as seems good to themselves, than by compelling each to live as seems good to the rest.

Like Bentham, Mill was a strong proponent for social reform, and often cited his view of Utilitarianism as a way to promote virtue as an ultimate utility. Mill furthered this aim by asserting that humans are naturally social creatures, and thus, must possess an interest in virtue in order to produce the most pleasure. In this way, Mill went a bit further than Bentham in citing human psychological states such as guilt and shame as partial measurements of an act’s utility.

Driver, Julia, “The History of Utilitarianism”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2014/entries/utilitarianism-history/>.

The Modern Day Consequentialist

Before becoming a hedonistic utilitarian in 2014, Peter Singer was first concerned with people’s preferences. In other words, in order to make an ethical decision we must take everyone’s preferences into consideration. Thus no gender, race or species has more preference than another in their right to gain pleasure.

Peter Singer has used this form of utilitarianism as a champion for animals (Animal Liberation) and nations in poverty (Famine, Affluence, and Morality). In the same way you or I may prefer to eat, or prefer not to die, animals and persons in other countries also prefer the same thing. Thus, we as humans have a moral responsibility to help those in need.

To be a utilitarian means that you judge actions as right or wrong in accordance with whether they have good consequences. So you try to do what will have the best consequences for all of those affected.

Peter Singer tells us we should stop eating animals aka become vegan, and he also tells us we should donate at least 10% of our income to charity. So that coffee you’ve been getting? Yeah… maybe you might want to start thinking about donating the money you spend on it instead. Oh, and skip the dairy creamer.

© Peter Singer, All Rights Reserved. https://petersinger.info/.