Hello new followers! I am moving this blog’s content + future content over to my other blog driftingbrain.wordpress.com in order for ease of access to my other academic (yet non-philosophy-related content) + in order to keep all of my works in a single location. I’d so appreciate if you could follow me over there!

Author: becca

Consider Humanity to Be an Error, a thought experiment

Does anything we do really matter? The general idea people seem to have is that we are all on some sort of journey, struggling to achieve our goals and make something of our lives, but doesn’t this only make sense if our achievements will last permanently? Eventually, even if you do produce some great work of literature or art, it will eventually perish with the rest of the Earth and the solar system. Thus, we arrive to our topic of discussion, what the hell are we doing here? Could it be, behind every thought, every laugh, every tear, that the source of these things is actually pure happenstance? Could it be the case that we are nothing more important than our bowel movements?

We considered this idea at our last philosophy meetup (09/05/19) with a thought experiment. The discussion proved an arduous task, as many both past and present philosophers are plagued by the absurdity of human existence. Nonetheless, we will power through and attempt to do the topic justice, here!

Consider Humanity to be an Error

How often have we been told that we are exceptional! Center of the world, children of God, universal consciousness, salt of the earth, intelligence, language-beings, spirit of science, vector of progress. Our existence has been so celebrated by myths, religions, philosophies, smug ideologies, that it is hard to comprehend our failures, our vileness, our interminable wars and our endless filth. Naturally, there has been any amount of special pleading, to explain our fall, our malediction, and our two-facedness.

There is a way of experimenting with a more radical form of absurdity. Rid yourself of anything that resembles a meaning to our existence. Consider humanity as a result of pure chance, a biological accident. It developed without order, on some lost pebble in some small benighted corner. One day it will disappear forever, unremembered and unmourned. For the tens of thousands of years of its survival, our species stagnated. Then it multiplied unreasonably, and plundered its own habitat. And before disappearing, it will have charged to its account a weight of suffering both unimaginable and futile, massacres and famines, enslavements and tyrannies.

Astonish Yourself! 101 Experiments in the Philosophy of Everyday Life. Written by: Roger-Pol Droit

Take a clear-eyed look at this absurd and violent species. Confront its lack of justification and its ephemeral, irrational existence. Train yourself to endure this vision of humanity as fundamentally meaningless and futureless. This should contribute to your serenity. Against this background of meaninglessness and horror, every sublime thing turns out more as a unique, unexpected gift. Perfect music, unforgettable paintings, the glory of cathedrals, grief-stricken poems, lovers’ laughter… Such are the endlessly surprising fruits of this narration that is us.

What does it all mean?

This thought might come to you as quite a shock to the system. Some might state that denying a teleological sense of purpose, or discussing the “endless filth” of humanity is a realistic, perhaps pragmatic stance to take in the debate, while others might call it plain pessimistic and unhelpful.

To think that the world has no meaning, is a form of faith in its own right. It is a secular response to issues that seem to require the human soul and spirit. Man, as the meaningless man sees him, cannot help but measure all he thinks and does in terms of these unearthly, higher, ideals; yet he can neither define them or attain them. And this, in the end, is the nature of “the human situation”: man is doomed to strive, to seek, and not to find– and yet he must not stop.

Paraphrased from: “Cosmic Hypochondria” The Love of Anxiety and Other Essays. Written by: Charles Frankel

Perhaps it is the case that we can all explain our reasons for doing the things that we do. We all eat because we are hungry, or sleep when we’re tired– the problem lies in the fact that, although there are justifications and explanations for most of the things that we do within our lives, none of these explanations will explain the point of our lives in their entirety. I’m talking about the whole of which all of these activities, successes and failures, strivings and disappointments are parts. While of course we all matter to people who care about us, at the same time, these people are still living within a finite world, and so their caring will also eventually cease to matter in the whole scheme of things.

Moreover, for every caustic account of humanity as a negative, consequence of nothingness, there are also accounts using the same evidence to prove the opposite point. How might all of this have come from absolutely nothing? How might that have been produce out of absolute darkness, infinite chance and possibility? Or perhaps, this is exactly what is required to produce humankind and its relatives. Then we must think, we can’t possible be the only ones living out there, somewhere. The chance of us being alone here, well, those are almost as slim as the mere fact that we even exist in the first place!

But still, we ponder… does it matter?

Does it matter that it doesn’t matter? Maybe we are all okay with this thought that things have no meaning. There are various ways your life could have a larger meaning. You might be a supporter of a political or social movement which changes the world for the better. Or you might just have prepared a good life for your family and their families. Or maybe your life is given meaning by religion and God, so your time here on Earth is considered to be a preparation for an eternal life somewhere else.

The thing we naturally ask a result to these, though, is once again, What is the meaning to even these? What is the whole point of these things in the grand scheme of things? What is the point in thinking that there is an eternal life?

The idea of God seems to be the idea of something that can explain everything else, without having to be explained itself. But it’s very hard to understand how there could be such a thing. If we ask the question, “Why is the world like this?” and are offered a religious answer, how can we be prevented from asking again, “And why is that true?” What kind of answer would bring all of our “Why” questions to a stop, once and for all? And if they can stop there, why couldn’t they have stopped earlier?

Even if human life as a whole is meaningless, perhaps that’s nothing to worry about. Perhaps we can recognize it and just go on as before. Perhaps all justifications can just come from inside of our experiences in this life. While some fully accept this view and use it to create their own meaning in life, others take themselves too seriously and become dissatisfied because they feel as though they haven’t lived up to their calling… but can we say there was ever a calling in the first place?

For Further Reading: Nagel, Thomas. What Does It All Mean? A Very Short Introduction To Philosophy.

Questions for further analysis & discussion

- Do you find any resistance to giving this idea any weight? Where do you think that feeling comes from, if so?

- If human life is meaningless is that something to worry about?

- Do we create our own meaning? Is this view incompatible with belief in God?

- What is the role of God as an ultimate explanation? Can there really be something which gives point to everything else by encompassing it, but which couldn’t have, or need, any point itself?

- What do you think of this attitude of seriousness that many people have? How have your views changed or remained the same over time about needing to attain some sort of set goal that was “meant” to be?

- If life has a self-created meaning, how does that help us to interact with one another?

- How might this view affect the origin of our views of what is right and wrong?

- How do you compare your concept of meaning now, with that of the concept you held when you were younger?

Utilitarianism: A Theory of Consequences

Imagine this scenario: you had a damn good day today. This morning you got a free ice cream cone, a free ticket to the nicest hotel in your area, and you even won a pair of VIP concert tickets to your favorite band’s performance, which had been sold out since last year. Since you are rightly pumped about this day you decide to take the scenic route by the railroad tracks on your way home from work. However, you see something peculiar along the split track…

One person is tied to the railroad track. You aren’t close enough to hear their screams, but upon further observation, you realize that on the other track there are five people tied up! For a moment you begin speculating about the reality of the situation, though this thought is cut short as you notice the train barreling down the tracks towards the five people, who are really screaming and crying now.

Unfortunately, this is where your lucky day takes a turn for the worst. You are the only one around to see this horrendous accident, and you’re way to far to reach everyone in time. Although, you do notice one peculiar thing… the conductors box is right next to you– meaning the train is controlled externally! You have the opportunity to change which track the train travels over. Will you flip the switch so that it heads towards the single individual tied to the track, or will you leave it be to kill the five people already in its grasps?

This ethical dilemma is known to many philosophers as the Trolley Problem. The dilemma here attempts to reach a solution to the nature of how one ought to make a moral decision.

The way in which one may approach the Trolley Problem depends quite a bit on the moral dimensions that one determines to be most relevant. Some aspects of this problem that a philosopher could deem as relevant include: number of people killed, contributions to society made by those whose lives are at stake, morality of those involved (eg, are there any doctors or political figures on the track), personal investment in those on the track (eg, is you mama on that railroad?!), etc. So you see how ethical discussions can become incredibly muddled as a new layer of the potential solution is discovered? While some may believe that the moral thing would be to save the many over the few, others may assert that there is always something inherently wrong with killing no matter how many you might save.

You might have no qualms about pulling the lever as you feel that benefit to the number of people you will save outweighs the harms of killing one person. If you think this, you might be a Utilitarian!

Utilitarianism is a theory that holds that the best way to make a moral decision is to look at the potential consequences of each available choice, and then, one should pick the option that either, does the most to increase happiness, or does the least to increase suffering. Utilitarianism, also known as consequentialism, is often summed up as a philosophy of “The greatest good for the greatest number.”

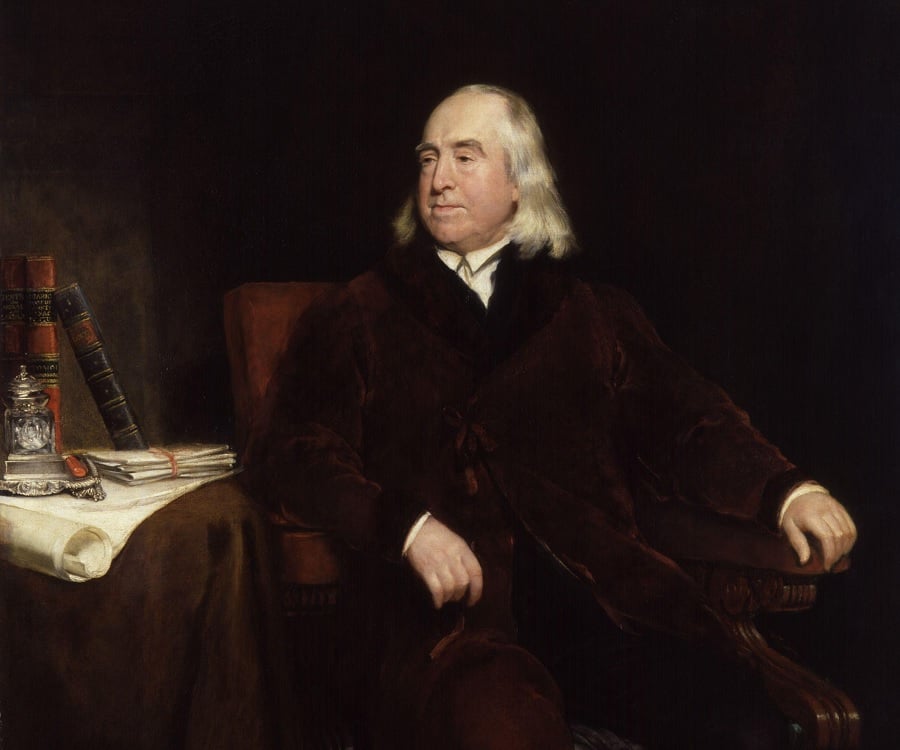

Pioneers of Utilitarianism

Bentham, widely considered one the greatest philosophers of the 19th century, was unsurprisingly, a child prodigy. By the age of three, he began studying scholarly texts, and just a few years later, he began to study Latin and Greek. At the age of 12, Bentham entered Oxford University and begin training as a lawyer, where he first began picturing how he might reform the political structure of society.

Create all the happiness you are able to create: remove all the misery you are able to remove. Every day will allow you to add something to the pleasure of others, or to diminish something of their pains. And for every grain of enjoyment you sow in the bosom of another, you shall find a harvest in your own bosom; while every sorrow which you pluck out from the thoughts and feelings of a fellow creature shall be replaced by beautiful peace and joy in the sanctuary of your soul.

Bentham often emphasized the instrumental measurement of happiness in an act: acts which lead to the most measurable utility (pleasure) are good acts, while those which lead to pain are not. An act is wrong, or right, according to Bentham, inasmuch as it results in a decrease or an increase of overall happiness. In other words, Bentham rejected the notion that any act could be intrinsically wrong or right regardless of consequences.

Moreover, as a strident proponent of social reform, Bentham maintained his Act Utilitarian view by differentiating between moral antipathy to an act and physical antipathy to an act. An example of such is Bentham’s take on homosexuality. He specified that the act in itself gives the homosexual person pleasure, whereas the pain that the dissenting individual feels is not of a moral nature, but rather a preferential one. To this Bentham might say.. “What’s it to you? Look away then.” This idea further resonates with Bentham’s assertions that no act in and of itself is wrong– rather the negative, or immoral, consequences that stem from an act may prove it to be.

Bentham recommended measuring utility in the observation of seven different characteristics associated with a certain act:

- intensity: how strong the pleasure or pain is

- duration: how long it lasts

- certainty: how likely the pleasure or pain is to be the result of the action

- proximity: how close the sensation will be to performance of the action

- fecundity: how likely it is to lead to further pleasures or pains

- purity: how much intermixture there is with the other sensation

- extent: the number of people affected by the action

Driver, Julia, “The History of Utilitarianism”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2014/entries/utilitarianism-history/>.

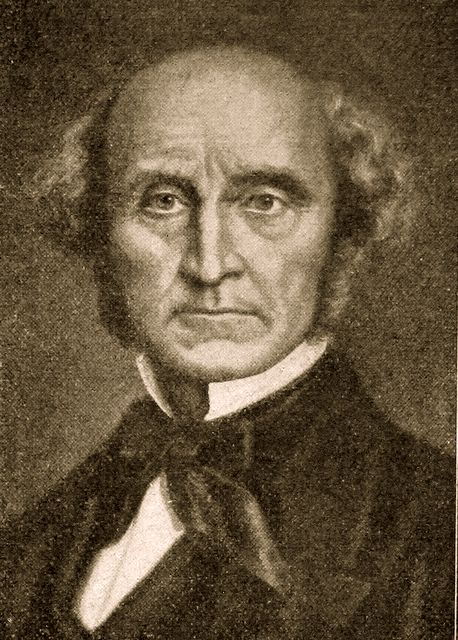

Child prodigy 2.0, John Stuart Mill began speaking Latin by the age of three. By the age of 16, he had a pivotal government position, and by the age of 20 he had a mental breakdown… relatable.

Mill often criticized Bentham’s approach as too egalitarian. Mill, instead, believed that there were “higher” forms of pleasure, more virtuous than those of a “lower”, animalistic nature.

Mill might argue that reading a book is more virtuous a pleasure to seek than is drinking a cranberry vodka. In that same vain, perhaps it is better to be a human in suffering, rather than a swine happily rolling in mud. In this way, Mill asserted that this hedonistic tendency in humans is intuitive in a perfectionistic sense, almost. No wonder Mill had a breakdown!

The only freedom which deserves the name is that of pursuing our own good in our own way, so long as we do not attempt to deprive others of theirs, or impede their efforts to obtain it. Each is the proper guardian of his own health, whether bodily, or mental or spiritual. Mankind are greater gainers by suffering each other to live as seems good to themselves, than by compelling each to live as seems good to the rest.

Like Bentham, Mill was a strong proponent for social reform, and often cited his view of Utilitarianism as a way to promote virtue as an ultimate utility. Mill furthered this aim by asserting that humans are naturally social creatures, and thus, must possess an interest in virtue in order to produce the most pleasure. In this way, Mill went a bit further than Bentham in citing human psychological states such as guilt and shame as partial measurements of an act’s utility.

Driver, Julia, “The History of Utilitarianism”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2014/entries/utilitarianism-history/>.

The Modern Day Consequentialist

Before becoming a hedonistic utilitarian in 2014, Peter Singer was first concerned with people’s preferences. In other words, in order to make an ethical decision we must take everyone’s preferences into consideration. Thus no gender, race or species has more preference than another in their right to gain pleasure.

Peter Singer has used this form of utilitarianism as a champion for animals (Animal Liberation) and nations in poverty (Famine, Affluence, and Morality). In the same way you or I may prefer to eat, or prefer not to die, animals and persons in other countries also prefer the same thing. Thus, we as humans have a moral responsibility to help those in need.

To be a utilitarian means that you judge actions as right or wrong in accordance with whether they have good consequences. So you try to do what will have the best consequences for all of those affected.

Peter Singer tells us we should stop eating animals aka become vegan, and he also tells us we should donate at least 10% of our income to charity. So that coffee you’ve been getting? Yeah… maybe you might want to start thinking about donating the money you spend on it instead. Oh, and skip the dairy creamer.

© Peter Singer, All Rights Reserved. https://petersinger.info/.

10 Common Logical Fallacies

Fallacies are errors in reasoning that render arguments to be illegitimate or weak.

Fallacies often appear in everyday conversation, the news, and even some academic writings. Often people make fallacious arguments as though they are actually proven facts, but it’s important to remember that this is not the case.

In fact, some arguments, though they may use factual reasons, can still lead to conclusions that do not logically follow from the reasons given. Others use premises that are based on falsehoods (stereotypes, assumptions, opinions, etc,).

Why do you think it’s important to have a good understanding of logical fallacies?

Reasons to avoid logical fallacies in conversation:

- Logical fallacies are wrong and, simply put, dishonest if you use them knowingly.

- They take away from the strength of your argument.

- The use of logical fallacies can make those you communicate with feel that you do not consider them to be very intelligent.

(William R. Smalzer, Write to Be Read: Reading, Reflection, and Writing, 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press, 2005)

- “Whether examining or writing arguments, make sure you detect logical fallacies that weaken arguments. Use evidence to support claims and validate information—this will make you appear credible and create trust in the minds of your audience.”

(Karen A. Wink, Rhetorical Strategies for Composition: Cracking an Academic Code. Rowman & Littlefield, 2016)

Where might you find some widely-accepted, yet fallacious, arguments?

Hint: The News!

Some common fallacies:

- Appeal to Popularity: Arguing that a claim must be true merely because a substantial number of people believe it. [example: ‘Of course war is justified. Everyone believes that it’s justified.”]

- Appeal to Tradition: Arguing that a claim must be true just because it’s part of a tradition. [example: “Acupuncture has been used for a thousand years in China. It must work.”]

- Appeal to Ignorance: Arguing that a lack of evidence proves something. In one type of this fallacy, the problem arises by thinking that a claim must be true because it hasn’t been shown to be false. (Can’t prove anything with a lack of evidence) [example: ‘No one has shown that ghosts aren’t real, so they must be real.”]

- Burden of proof: Weight of evidence or argument required by multiples sides in a debate or disagreement. It’s important we prove claims beyond a reasonable doubt. What does this mean?

- Appeal to Emotion: Use of emotions as premises in an argument in order to persuade someone of a conclusion. [example: “You should hire me for this job because I am the best candidate. Also, if I don’t get this job my wife will leave me, and we’ve been together for over 30 years…”]

- Appeal to Pity: persuasion through pity

- Apple Polishing: persuasion through flattery

- Scare Tactics: persuasion through scaring them or evoking fear

- Red Herring: Deliberate raising of an issue during an argument that is totally unrelated to the conclusion. Other claims that couple the main claim are mere distractions. [example: “The legislators should vote for three-strikes-and-you’re-out crime control measure. I’m telling you, crime is a terrible thing when it happens to you. It causes death, pain, fear. And I wouldn’t want to wish these things on anyone.”]

- Straw Man: The distorting, weakening, or oversimplifying of someone’s position so it can be more easily attacked or refuted. [example: “President Kennedy is opposed to the military spending bill, saying that it’s too costly. Why does he always want to slash everything to the bone? He wants a pint-sized military that couldn’t fight off a crazed band of terrorists, let alone a rogue nation.”]

- Two Wrongs Make a Right: Arguing that you’re doing something morally wrong is justified because someone else has done the same thing. [example: “I have a clear conscious. I stole his laptop because he stole mine a couple of months ago.”]

- Slippery Slope: Arguing, without good reason, that taking a particular step will inevitably lead to a further, undesirable step. [example: “If you redefine marriage to include gay people, then suddenly we’ll be allowing people to marry their pets.”]

- Hasty Generalization: The drawing of a conclusion about a target group based on an inadequate sample size. [example: “The only male professor I had this year was a chauvinist pig. All male professors must be chauvinist pigs.”]

- Faulty Analogy: An argument in which things being compared are not sufficiently similar in relevant ways. [example: Dogs are warm-blooded, nurse their young, and give birth to puppies. Humans are warm-blooded and nurse their young. Therefore, they also give birth to puppies.]

Rivers Are People Too!

During a meeting on 8/17/2019, philosophers of the community discussed a case from the Intercollegiate Ethics Bowl Competition regarding the moral and practical implications of granting rivers legal personhood. Themes of the discussion included practical ethics, environmental ethics, philosophy of culture, religion, language and law. Three concepts that presented themselves in spirit during this discussion are important to note, as they have deep roots in the history of philosophy. These are utilitarianism, philosophy of language (specifically that of Wittgenstein), and philosophical egoism.

Enjoy!

Case 15: Rivers Are People Too

On March 15th, 2017, New Zealand passed a law declaring the Whanganui River a legal person. The Whanganui (JUANG–GUH–NEW–EE) is the first river to gain legal personhood, but India quickly followed suit and granted personhood to both the Ganges and Yamuna rivers. Court appointed guardians are now responsible for being trustees of the rivers’ rights. These rivers cannot vote or buy beer, but they now have legal standing in national courts. Maori (MOW-REE) spokesperson Gerrard Albert says of the legal recognition: We have fought to find an approximation in law so that all others can understand that from our perspective treating the river as a living entity is the correct way to approach it, as in [sic] indivisible whole, instead of the traditional model for the last 100 years of treating it from a perspective of ownership and management.

In addition to reflecting an ancestral view of personhood, there are practical advantages to the new legal status of the Whanganui and Ganges. Each day, around two billion liters of waste are deposited in the Ganges alone. No longer will attempts to protect the river’s health be required to show harm to people, because the rivers themselves will have rights. According to one source, “[t]he decision, which was welcomed by environmentalists, means that polluting or damaging the rivers will be legally equivalent to harming a person.”

However, these new protections have some people worried about the possible effects of protecting rivers on the local human populations. For instance, city sewage, farming pesticides, and industrial waste are all currently dumped into the Yamuna, and these waste products are, to some extent, an unavoidable aspect of urban development, farming practices, and industry. An immediate cessation of dumping this waste would adversely affect the people living in the area and benefiting from these industries.

[Case from the 2017 Regional Intercollegiate Ethics Bowl. © Association for Practical and Professional Ethics 2017 http://ethics.iit.edu/eb/RiversarePeopleToo.pdf%5D

Moral Dimensions:

- Philosophy of Personhood

- Personhood via Legal Representation

- Cultural Representation & Significance

Relevant Philosophical Concepts & Questions:

- Semantics of the term “Person”

- Psychological/Societal Egoism, or “What’s in our best interest?”

- What are the potential consequences of using “person”?

- Where do our ideas on personhood originate?

- If we call a river a person, where do we draw the line?

Philosophy of Personhood:

From proponents:

It is first important to differentiate a person from a human being. Rivers are not human beings, but we would like to assert that they could be persons. This requires us to, first, establish a working definition of the word person.

To be a person, one must be a subject of a life; to be a person, one must, at a basic level, contain a life– a life which can be good or bad (in relation to said person’s existence and in relation to the world in which it lives). For this reason, it is acceptable to consider a river as a person for legal, cultural and basic philosophical purposes.

Consequently, a human being is a person who additionally contains the potential to self-reflect, or to consciously interpret and analyze his/her/their experiences. This means that a human being is further able to acknowledge the fact that he/she/they can, or does, have a good or bad existence.

The river can have a life which can be good or bad. In asserting this we assert that it has personhood; it simply is a person. Further, one might state that the river has a certain level of interests like a person does, those being abundance, independence, and life. The river’s life is represented by the many creatures that inhabit it; the river’s “life” in essence, is contained in its ability support itself via natural means. It even carries a certain influence over human beings, and provides support that humans are otherwise unable to live without: water, food, resources, agricultural and economic support. So calling it a person is actually within our best interests, anyways.

From critics:

Rivers should have rights, but they should not be called persons. They should be protected under a different legal term.

The way in which the world currently is, does not intuitively account for a natural entity to be called a person. The way in which the word “person” is currently used in society truly dictates what we consider a person to be. Can we start calling mountains persons, too? Buildings and corporations are labeled as persons in a legal sense, but this it mainly done to hold the corporation accountable for its actions. There are people behind it, though they aren’t actually it themselves. We can’t hold a river accountable for flooding, can we?

Personhood via Legal Representation

From critics:

It seems that the only arguable reason to call a river a person might just be the practical reasons for doing so. However, does giving the river a sense of legal personhood really change the way in which humans will view the river? Harming the river will now be the legal equivalent of harming a person, but will it remain the moral equivalent?

People are naturally egocentric, meaning that many will not be able to give the river moral significance without a change in perception. Sure we may change our definition of personhood, but many will not understand, nor support this until they change their perception on the importance of our environment. Rather than labeling the river and protecting it as a person, might we find a more plausible way to invoke perceptual changes in society? Moreover, what is our definition of harm going to entail? A river can’t perceive that it is being harmed in the same way a person might.

From proponents:

The legality ensures that the moral significance of the river is established and maintained. Giving it a legal sense of personhood forces people to acknowledge the fact that the river has “interests”, and it also grants them the awareness to see that a natural entity that contains life doesn’t have to be like us in order to be important. In the same way we pass laws to protect animals, we would be doing so for the river.

Furthermore, touching on the question of harm: it can certainly be argued that persons– even those without rational faculties– are harmed everyday, subtly, by pollution emitted from cars and factories and even further by the very foods they consume. These are not absolute harms. So putting small amounts of pollutants into the river might be harmful in the sense that it might cause micro- consequences to the river, but none that are permanent or damaging to the long term wellbeing of the river. It is a bearable harm in that sense.

Cultural Representation & Significance

From proponents:

It is important to take into account the cultural significance of allowing the Maori people to protect and value this river. Treating the river as a living entity, an indivisible whole, rather than as a thing to be owned allows them to maintain a sense of united piety. Furthermore, the Maori people have an ancestral view of personhood, and as such, it is important to note that a socially-contrived definition of personhood must also take into account connotative variations existing in multiple languages, not only those of a Eurocentric worldview. In this way, the river, philosophically and culturally speaking, possesses a basic personhood.

From Critics:

We understand and respect the Maori culture’s worship of the river. In a lot of ways it’s true that the river has a higher sense of importance to it than humans do. The river sustains life– both human, animal, and plant. However, we must question whether or not granting the river a label such as person encourages duplicitous behavior in law and in language. It seems that the best case, to promote social and environmental harmony, would mean suspending the use of the word person until a legal and linguistic understanding of the word can be agreed upon.

A final thought from supporters:

In calling the river a person, we strongly assert that it’s life (well being) has moral significance. It is an independent and unified entity for which things can be good or bad. In asserting that there is moral weight to calling the river a person, we think that the point is missed if we do not call the river a person on a technicality as such as linguistic preference or tradition.

Thus, if in this case, it benefits the majority to call the river a person, and it makes the most sense in a legal & practical way, then in the very least the river should be called a person for the sake of the Maori people, the interdependence of those people on the river and the fact that this is simply the way things ought to be done based on the current state of law in this world. To write and propose and vote on an entirely new law simply because we have a technical objection to the term personhood, would sidetrack the environmental importance of passing such a law.

A final thought from critics:

There really doesn’t seem to be much of a disagreement, here, between us, other than semantically. We ought not call the river a person. While the technicality of the term, legally and spiritually speaking, might encourage us to do so for practical and ritualistic purposes, this does not mean that it in actuality is a person. Could an unintended consequence of this change be that us as humans begin to change our definitions as persons to fit whatever societal instrument we please? Is there not something intrinsic and immutable about keeping language with its intended use? In allowing for the meaning of words to preemptively transform, do we allow a sort of linguistic desensitization to erupt towards thinking, speaking, emotive creatures? The Maori and Ganges river deserve protection, but to do so under a guise of personhood is not the way to do it.

The Final Result!*

Call it a person: 2 philosophers

Protect the river, but don’t call it a person: 4 philosophers

Help me, I have no idea what I think anymore: 2 philosophers

Abstaining: 1 philosopher

What do you think?

*Indicates votes counted by those present at the meeting.